Summary: There’s more to the freemium business model than you think. And the only way to tackle it is by questioning the predefined assumptions that are attached to what a classical freemium business model should be (a free-forever plan with limited features/usage compared to the premium plan). Here’s how we learned this lesson from AWS’s take on freemium and our own failures and successes with the freemium model.

Begin challenging your own assumptions. Your assumptions are your windows on the world. Scrub them off every once in awhile, or the light won’t come in.

When Cirque du Soleil debuted in the early 1980s, the circus industry was taking a nosedive.

Circuses were busy pitting themselves against one another, by tweaking conventional circus standards like putting up animal shows, presenting top circus performers, hosting shows in multiple arenas, and selling aisle concessions.

These unwritten, expensive norms set by the then industry biggies, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, coupled with the advent of alternative entertainment forms like video games that caught the attention of kids, made it almost impossible for circus companies to hit a profit.

Until Cirque du Soleil stepped in and changed the rules of the game.

They broke away from almost all the major boundaries that had been ingrained in circus shows, like replacing saw-dust ridden hard-benched tents with grand, luxurious venues, taking away animals from the scene, and changing the humor of the clowns from slapstick to sophisticated.

They blended the thrill of the circus with the artistry of the theatre, redefined the problem, reinvented the circus, and morphed it from a cheap kids entertainment to an upscale experience for adults and corporates.

And in less than 20 years, Cirque du Soleil got to the revenue benchmark that Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey had taken over a century to achieve.

Challenging predefined and perceived notions that have been taken for granted in a particular system can unearth its inherent flaws and unravel umpteen growth opportunities.

And this very approach is what you need to tackle the seemingly shifty freemium model. Case in point, AWS. And we are going to see how they managed to do it.

Now, this is how the SaaS industry’s conventional wisdom — including us, in the past — defines freemium, a portmanteau of “free” and “premium”:

“‘Classical Freemium‘ is the marketing tactic where a SaaS or Web App vendor offers a Free-in-Perpetuity version of a product or service, often feature- or usage-limited, as well as a version of the same product or service with fewer limitations to which the vendor will attempt to up-sell the user.”

And this model’s two major assumptions/limitations are comfortably seated in that very statement.

Let’s break them down separately.

1. Freemium offers a free-in-perpetuity version of the product/service

I have some friends with whom I used to regularly snow-ski in Colorado. At the end of a run, we’d often ask each other “Did you ski the mountain or did the mountain ski you?” Of course, we all made it down the mountain, but what we were really asking each other was whether we were in control of our path or were we reacting to the bumps, trees, ice, fellow skiers, and other obstacles in the way

Baremetrics. Parse. Bidsketch. The interweb is ridden with horror stories of business whose free-forever plans miserably failed.

With an average conversion rate of 3-5%, the classical freemium model can lead to utter abuse of your product, if mishandled.

In the worst-case scenario, you’ll find customers flocking to and using your system for free, your infrastructure costs will go through the roof and eventually drain out your pockets, if you don’t have deep ones.

We lost nearly 60 customers during the 11 weeks we had our free plan, doubling our revenue churn and resulting in a net loss of customers. Our free plan was causing our business to slowly implode.

And unlike a pricing experiment, a freemium model needs a good three to six months to find out if you’re on the right track. And time is the biggest constraint and the costliest resource for an early stage startup.

However, on the flip side, you have the freemium poster-children like Buffer, Dropbox, and Typeform most of whom sport a free-forever plan and seem to be doing just fine.

Here’s the thing, your product isn’t Dropbox. Neither is it Baremetrics. So what worked or backfired for them might or might not cut it for you.

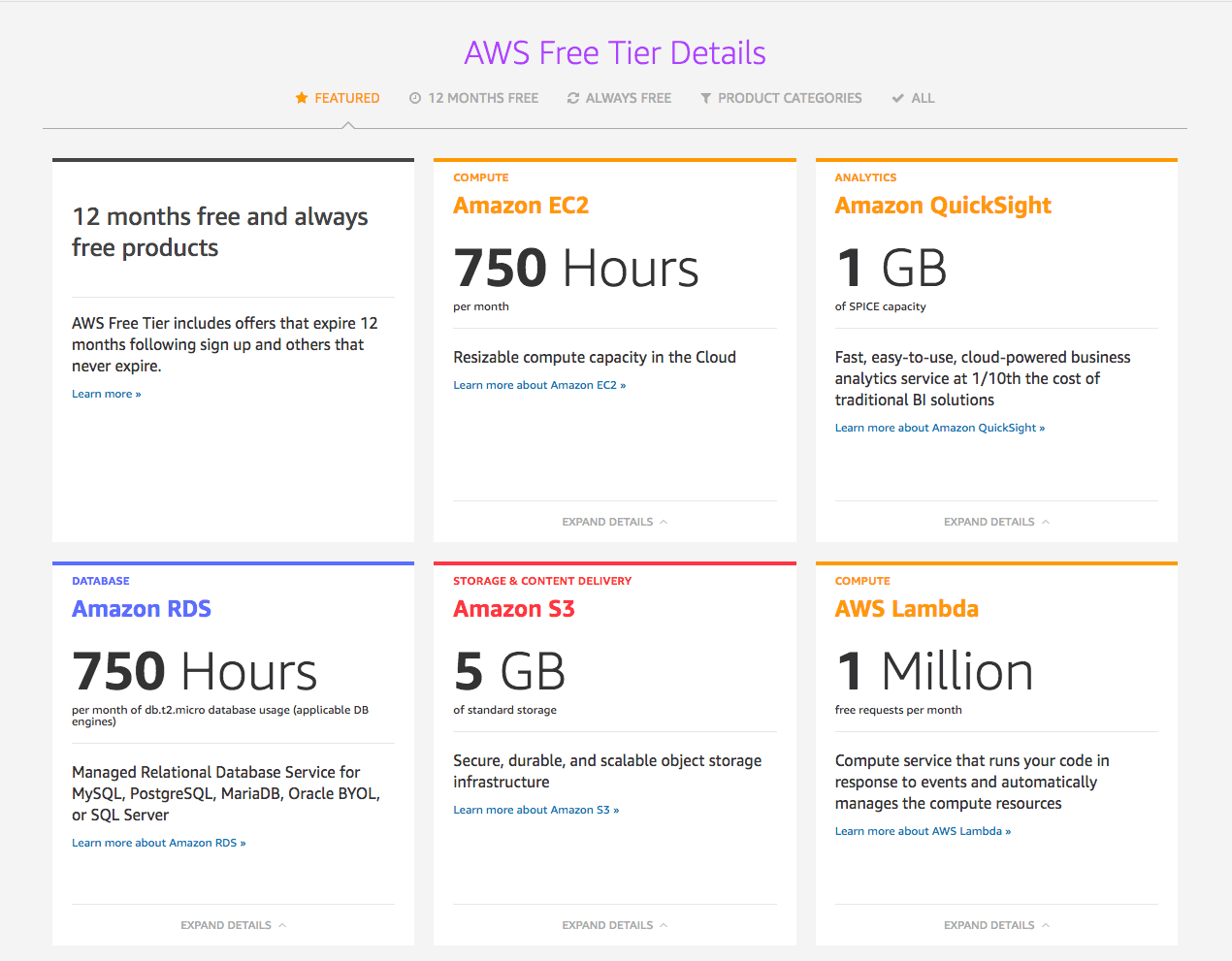

In their freemium plan, AWS (even though they have a pocket as deep as the Mariana Trench) offer a year’s worth of micro instance for free – a time-bound freemium model.

They’re giving away an instance for a year with your card details already saved in your account, so that if you continue to use the service beyond the first year, they’ll automatically start charging you. It’s almost like an extended free trial.

Now you might ask, why one year? Why not bring it further down to, say a month?

We’ve got two words for it – product-model fit.

For a product like AWS, a free trial for say 30 days will be too short a time for them to deliver value and for the customer to experience it.

AWS needs adequate time to get a skeptical developer to understand the value that they offer, to get the developer hooked to the product and build on top of it, and to eventually recommend them to a fellow developer.

So instead of getting unnerved by the failure stories or overconfident by the success tales, ask yourself these questions to help you frame your freemium model:

How will your product demonstrate its value? How long will it take for a customer to realize it? And how will you shape your freemium strategy around this in such a way that the moment the customer understands the value, your product nudges them to move up to a paid plan?

2. The free version is feature- or usage- limited

Summarizing this entire section in one sentence – pick the wrong value metric for your freemium plan and you’ve found yourself the perfect recipe for disaster.

And the value metric needn’t be based on feature sets all the time. While feature-based pricing aligns perfectly with Webflow’s product and business model, Dropbox uses storage space as its value metrics and AWS employs time.

If we go back eight years, before AWS went mainstream, we had a lot of developers who argued that AWS was completely unnecessary and that they would do just fine without it.

Now, there are two ways in which AWS could have handled this situation.

One, go all out and challenge their beliefs by talking to them about the value and keep pushing that message through case studies, customer testimonials, demos, etc. It’s an effective approach, yes, but will get harder and harder as they scaled.

Two, not fight the developer’s ego and instead give away the product for free for them to look for the value and justify if they’d still be able to do AWS’s job by themselves. By going down this road, they’ve actually turned the tables where they no longer have to win the argument.

Meanwhile, you have also gotten your foot in the door and can leave it there for a sustained period of time – enough time for you to deliver value in a way that you implicitly win them over.

Just like almost all other aspects of the freemium model, there’s no one-size-fits-all value metric. And until you nail the right value metric, your freemium model will always be amiss.

And we had to learn this lesson the hard way.

In our first freemium plan that we had launched in 2013, we picked the number of invoices as our value metric, and, boy, how did that turn out.

We were giving away the first 10 invoices for free, every month. And the moment the eleventh invoice for the month was raised, the customer was moved to a paid plan.

And as it turned out, this model (value metric, to be specific) was attracting the wrong kind (and deterring the right kind) of customers.

We were acquiring customers like consulting companies who never had more than 10 clients to be charged on a monthly basis.

These customers regarded Chargebee as a recurring invoicing system which allowed them to bill their customers for free forever and didn’t find enough value to pay the full price just for the sake of one extra customer/invoice.

In short, they hardly converted to a paid plan.

An ideal customer is someone who’s requirements perfectly align with the value of your product. Someone who has a clear understanding of how a subscription billing system will help them grow their business. Someone who wouldn’t argue that they’d might as well use a recurring invoicing system like Xero or Quickbooks.

The meager conversion rate aside, attracting the wrong segment of customers poses another critical threat as well – it will derail your product’s evolution.

If you’re going to prioritize and build the features that are required for your fringe customers, who will, in fact, be using those features rather sparingly and will never upgrade in terms of receiving value, you’re inadvertently failing to build features that will cater to your ideal customers.

Within six to nine months of launching it, we realized that our 2013 freemium model was fundamentally flawed – we were gaining the wrong set of prospects who were sabotaging the product as well as the business.

We course-corrected, took a leaf out of AWS’s playbook, and introduced a revised version of the freemium plan, where the customer’s first $50k in revenue is on us.

It’s not free forever, it’s not a feature-based value metric, and yet it fits OUR product like a glove.

$50k is a neat revenue benchmark for startups – till you hit that number, you probably will not possess adequate conviction for the idea and would still be in the experimental phase, and the moment you hit that threshold, you’re more likely to take the plunge and pursue it as a full-fledged business.

And by the time you reach that stage, you’d have already gotten used to having a system that takes care of all your subscription management and billing needs, that you’d rather prefer to let that keep doing whatever it has been doing and focus on the other aspects of your business.

Long story short, your product should dictate your freemium model, and not the other way around.

Cirque du Soleil broke the best practice rule of the circus industry, achieving both differentiation and low cost by reconstructing elements across existing industry boundaries. The Cirque du Soleil, then, really a circus, with all that it eliminated, reduced, raised, and created.? Or is it a theatre? And if it is a theatre, then what genre – a Broadway show, an opera, a ballet? It is not clear. Cirque du Soleil reconstructed elements across these alternatives, and, in the end, it is simultaneously a little of all of them and none of any of them in their entirety. It created a blue ocean of new, and contested market space.

Conclusion:

It doesn’t matter if you pick a value metric that has never been picked by a fellow SaaS company before.

It doesn’t matter if the time span of your freemium plan is radically different from all the plans that have ever existed in your industry.

It doesn’t matter if your freemium plan looks very little like one.

As long as it aligns with your product and the value that it offers.

Shift your mindset, step out of the pre-defined boundaries, and fit the model with your product (instead of the other way around). Decouple the “free” in the freemium, analyze it, and break down the pre-established silos in this notoriously mishandled model. And watch it thrive.

Of course, there are numerous other assumptions/norms/limitations that are waiting to be discovered and challenged.

Have you found any? If yes, how did you handle (or wish you had handled) them?